Events and News

Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB)

Overview

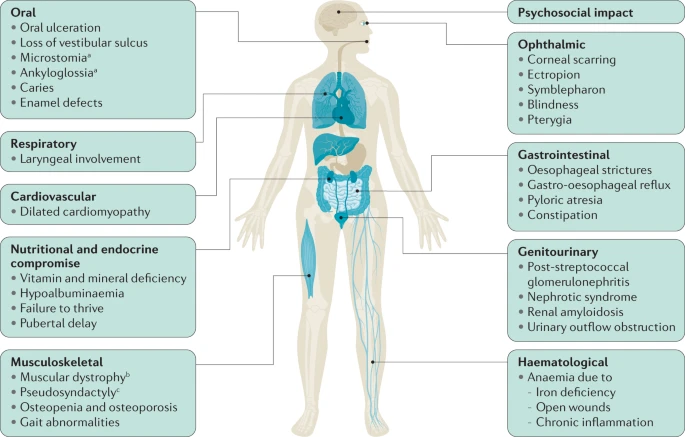

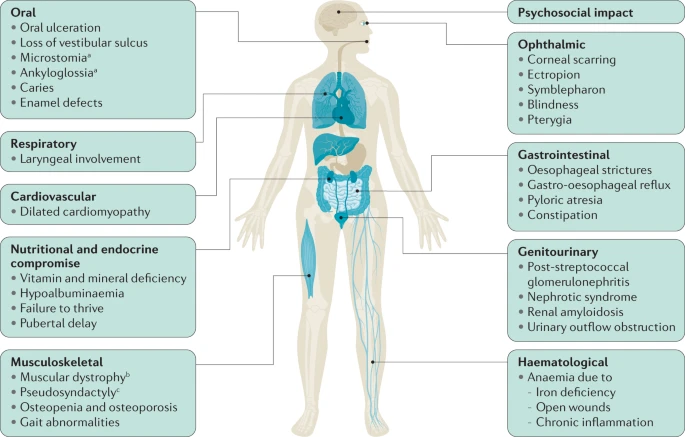

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a rare genetic skin disorder associated with chronic ulcers. EB makes the skin so fragile that any friction, mild trauma, and wound to the epidermis can lead to painful blisters. (Figure 1) (1). Although EB is a rare condition, its prevalence is 1-25 per million population, and it has an incidence of 2-54 per million live births. (2) Due to the delicate nature of the skin, children with EB are often referred to as “Butterfly Children”, drawing a comparison to the fragile wings of a butterfly. (1) Unfortunately, EB has no cure, and all the treatments are limited to managing, preventing and alleviating its complication. (2)There are four types of EB: EB simplex , junctional EB, dystrophic EB and Kindler EB. (3) Apart from wound healing complications, based on the subtype and the affected protein, patients may suffer from different complications. For example, some patients may develop squamous cell carcinomas (2) or in severe cases, EB can extend beyond the skin, affecting other organs. (Figure 2) (1,10)

Figure 1) EB is associated with skin erosion and painful blisters. (1)

Figure 2). In severe cases, EB can affect other organs and systems besides the skin. (10)

____________________________________________________

Aetiology

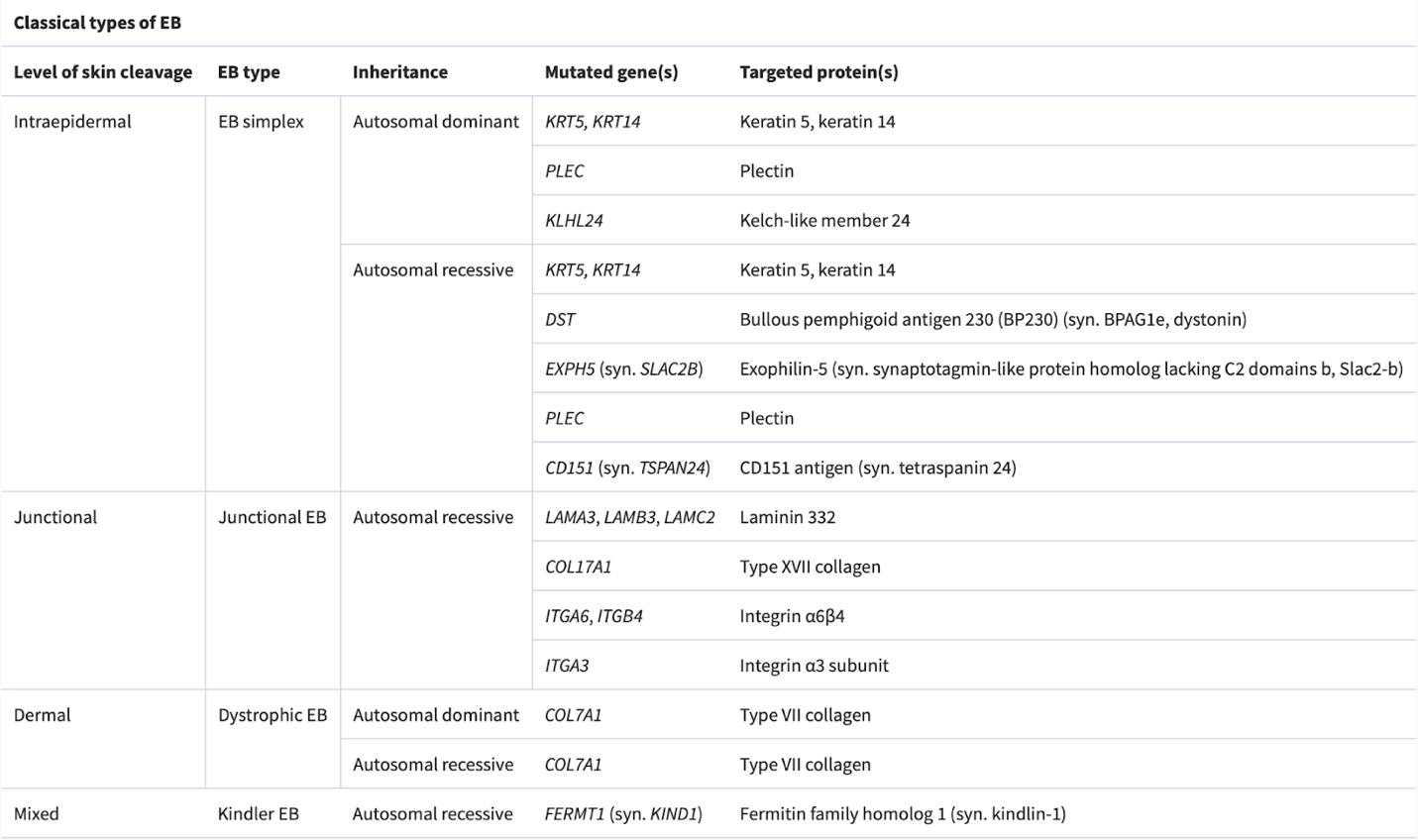

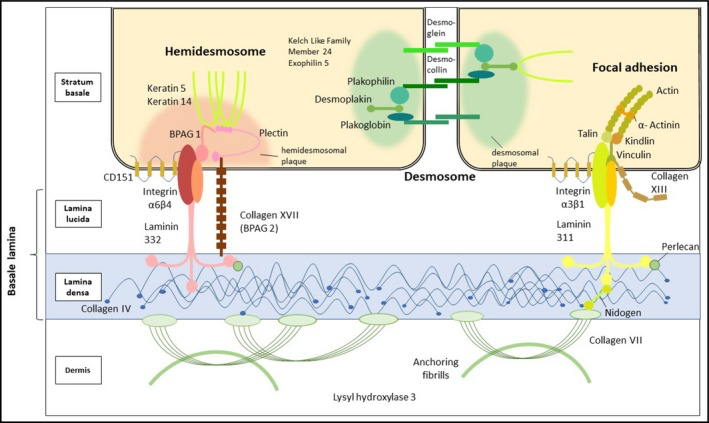

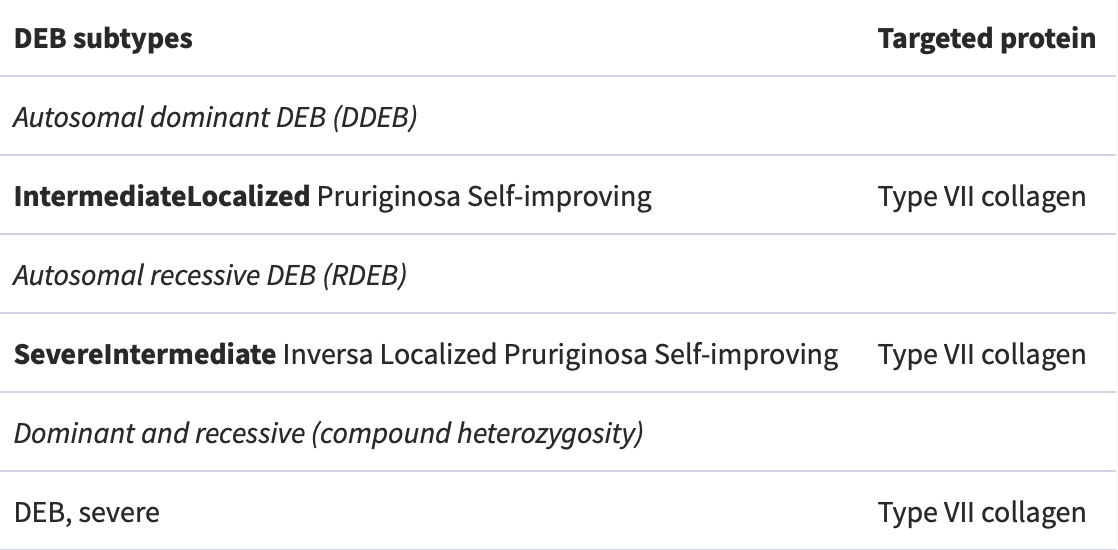

Based on the structural level of skin cleavage and blistering, there are four types of EB; each has its specific gene mutations. (Table 1 and Figure 3)

- Epidermolysis bullosa simplex

- Junctional epidermolysis bullosa

- Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa

- Kindler epidermolysis bullosa

Epidermolysis bullosa simplex Aetiology

Epidermolysis bullosa simplex is the most common type of EB, characterised by intraepidermal blistering. It is caused by mutations in genes responsible for keratin proteins, essential for skin strength and resilience. (5)

Junctional epidermolysis bullosa Aetiology

Junctional epidermolysis bullosa is a more severe form of EB, where blistering occurs at the junction between the epidermis and the underlying dermis (at lamina lucida of the cutaneous basement membrane zone). It is caused by gene mutations related to laminin or collagen XVII, vital for anchoring the skin layers together. (6)

Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa Aetiology

Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa is caused by mutations in genes involved in collagen VII production, a crucial component of anchoring fibrils that help attach the epidermis to the underlying dermis. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa is characterised by subepidermal blistering and can lead to severe scarring. (7)

Kindler epidermolysis bullosa Aetiology

Kindler epidermolysis bullosa is a rare form of EB, characterised by blistering at multiple skin layers due to mutations in the FERMT1 gene. It results in a range of skin symptoms and photosensitivity. (8)

Table 1) Subtypes of EB with their related affected genes. (3)

Figure 3) A view of different skin layers and their associated proteins. Some of the affected proteins in EB can be observed here. Such as Keratin 5, keratin 14, Plectin, Kelch-like member 24, Keratin 5, keratin 14, Exophilin-5, Laminin 332, Type XVII collagen, Integrin a6ß4, Integrin a3 subunit, Type VII collagen. (4)

____________________________________________________

Symptoms and clinical diagnosis

Based on the classic clinical categorisation of EB, different symptoms can be seen in each subtype. Let’s take a look at the symptoms associated with each subtype.

Epidermolysis bullosa simplex symptoms and clinical diagnosis

1)Neonatal severe Epidermolysis bullosa:

- Extensive skin blistering, ulceration, and crusting

- Thickened nails

2)Severe Epidermolysis bullosa beyond infancy:

- Arcuate or herpetiform blistering and crusting on an inflamed base

3) Localised Epidermolysis bullosa:

- Tense blisters and healing erosions on friction sites, primarily affecting the feet

4)Severe Epidermolysis bullosa (common to all three subtypes):

- Plantar keratoderma (thickened skin on the soles of the feet)

5)Severe Epidermolysis bullosa (nail involvement):

- Thick and deformed nails

6)Epidermolysis bullosa with mottled pigmentation:

- Mottled hypo‐ and hyperpigmentation on the lower abdomen

7)KLHL24 Epidermolysis bullosa:

- Superficial crusts, erosions, and scarring

Junctional epidermolysis bullosa symptoms and clinical diagnosis

Junctional epidermolysis bullosa is characterised by the following:

- Nail loss, along with skin blistering and crusting

- Scarring and nonscarring alopecia, resulting in patchily sparse hair

- Dental enamel defects and discoloured, pitted teeth are common features.

- Newborns experience skin blistering and crusting, and they often exhibit Typical granulation tissue in the distal digits, face, and ears.

Localised, dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa and intermediate recessive epidermolysis bullosa symptoms and clinical diagnosis

These two types usually have the same symptoms, including:

- Skin blistering is often confined to specific areas, primarily the acral regions and bony prominences like elbows and knees. The blisters heal, leaving behind scars.

- Nail abnormalities or loss

Severe recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa symptoms and clinical diagnosis

Neonates experience widespread skin fragility, leading to frequent ulceration. The extensive blistering and wounds in affected individuals can result in scarring and joint contractures, impacting their range of motion and mobility. As patients grow older, they may face additional challenges, such as losing distal digits, digital fusion, and increasing flexion contractures. Squamous cell carcinoma is common, especially on acral sites (extremities) and the lower limbs. Oral involvement is prevalent, with blistering and ulceration affecting the oral mucosa and a characteristic smooth, depapillated tongue. Over time, progressive oral mucosal scarring can lead to microstomia (a small mouth), loss of sulci (grooves in the oral tissues), and dental overcrowding, impacting speech and eating habits. Patients may also experience ectropion (outward turning of the eyelids) and pannus formation (abnormal tissue growth over the cornea), which can affect vision and ocular health. These ocular complications add to the overall burden of the condition and require close monitoring and management.

Kindler epidermolysis bullosa symptoms and clinical diagnosis

- The hands and neck show signs of skin thinning and poikiloderma.

- There is gingivitis (a common and mild form of gum disease that causes irritation, redness, and swelling of the gingiva, the part of the gum around the base of your teeth.) accompanied by excessive growth of gum tissue.

- Ectropion (the lower eyelid is turned outward and away from the eyeball. As a result, the edge of the eyelid does not make proper contact with the eye’s surface, which can cause eye problems and discomfort.) This is a frequent occurrence and may result in corneal erosions. (3)

____________________________________________________

Molecular Diagnosis

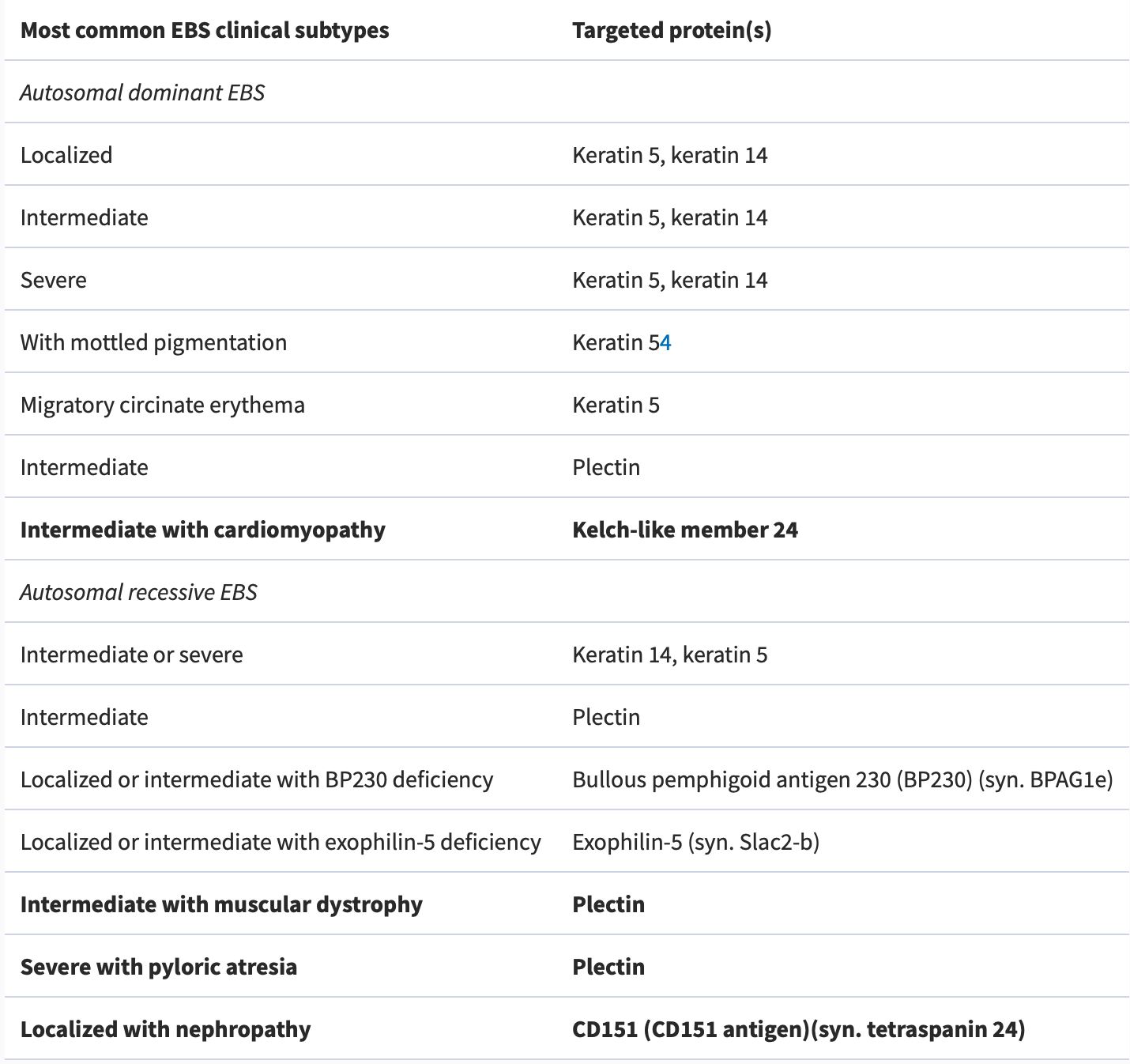

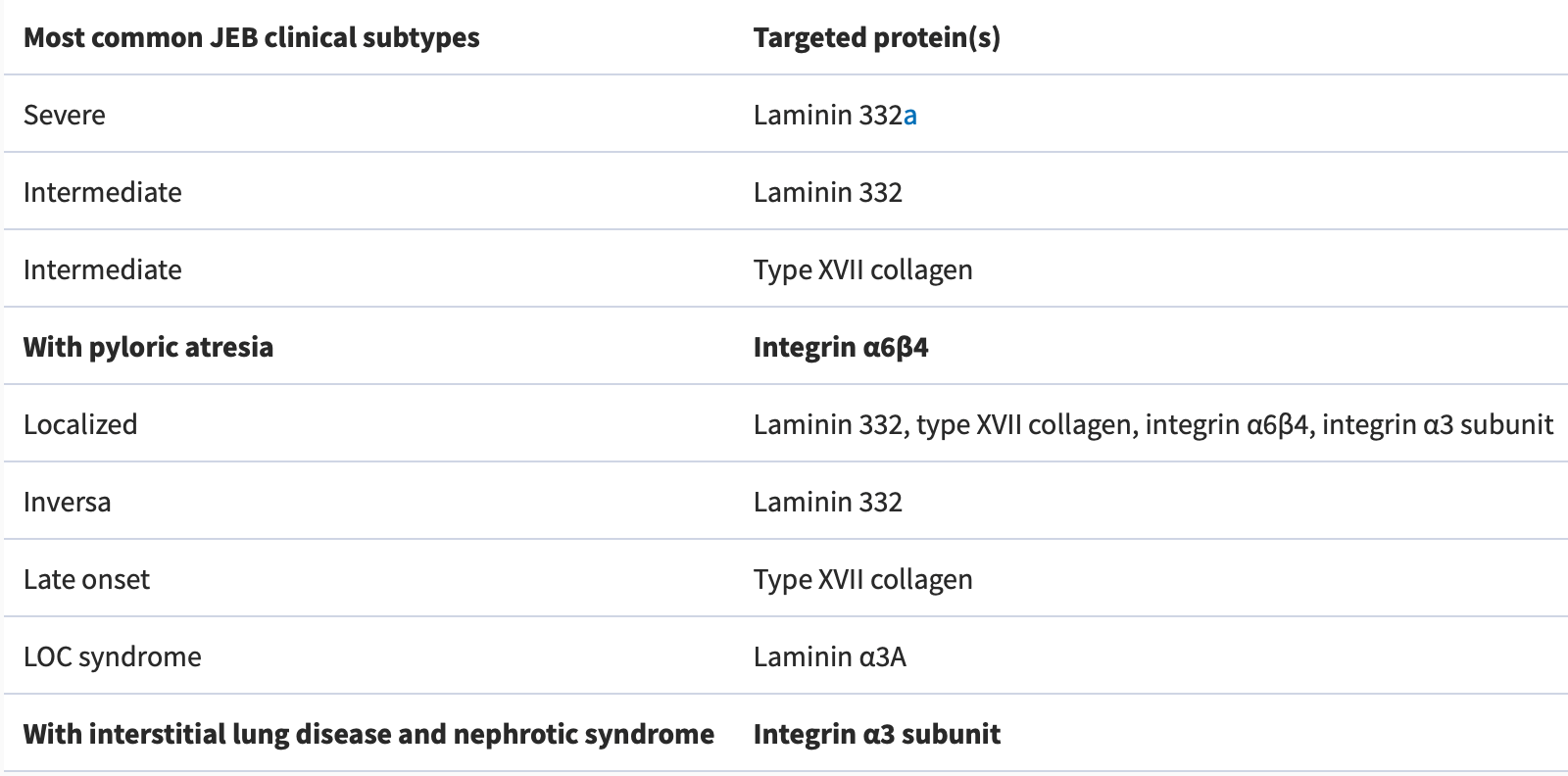

As EB’s symptoms appear at birth, usually EB diagnosed in childhood. However, in some mild cases, EB is diagnosed in adulthood. (3) EB is one of the subtypes of Genetic disorders with skin fragility; hence diagnosing merely based on the clinical features might not distinguish EB from other Genetic disorders with skin fragility. Therefore, a biopsy of the skin or blood sample must be checked for specific defective genes to have a precise molecular subclassification of the EB. (Table 2-5) Laboratories can use gene analysis methods like Whole‐exome Sequencing or Next Generation sequencing. Also, immunofluorescence mapping (Antigen mapping) (IFM) can be used to visualise the distribution of specific proteins or molecules. In addition, Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) can help in more detailed observation of the biopsy tissue. (3-4)

Table 2) Epidermolysis bullosa simplex subtypes (3)

Table 3) Junctional epidermolysis bullosa subtypes(3)

Table 4) Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa subtypes (3)

Prenatal Genetic testing

Prenatal testing, such as chorionic villus sampling, is available for families with a known genetic risk for EB. Since EB is primarily caused by genetic mutations, prenatal testing can be performed at the 11th week of gestation to identify whether the embryo has inherited EB. (9)

____________________________________________________

Pathological Features

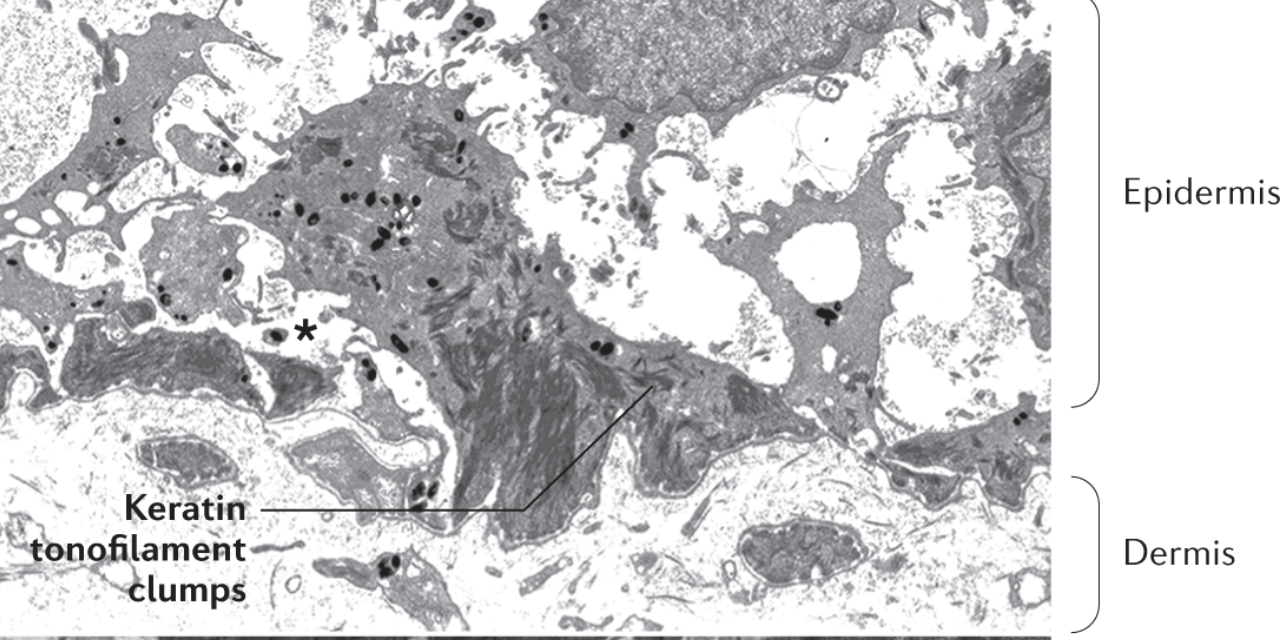

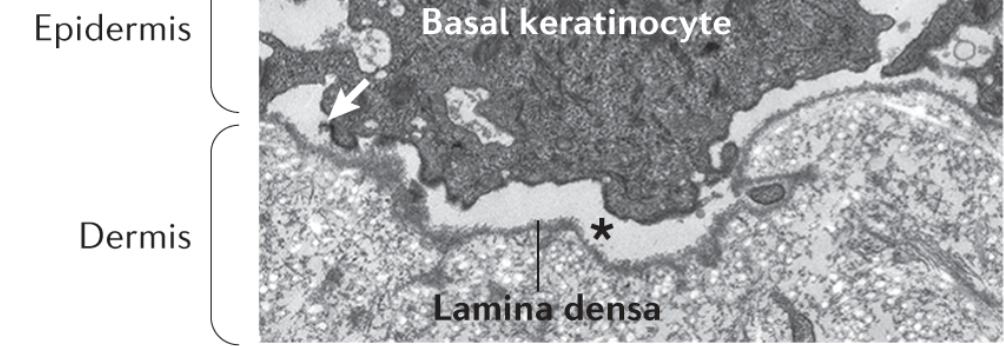

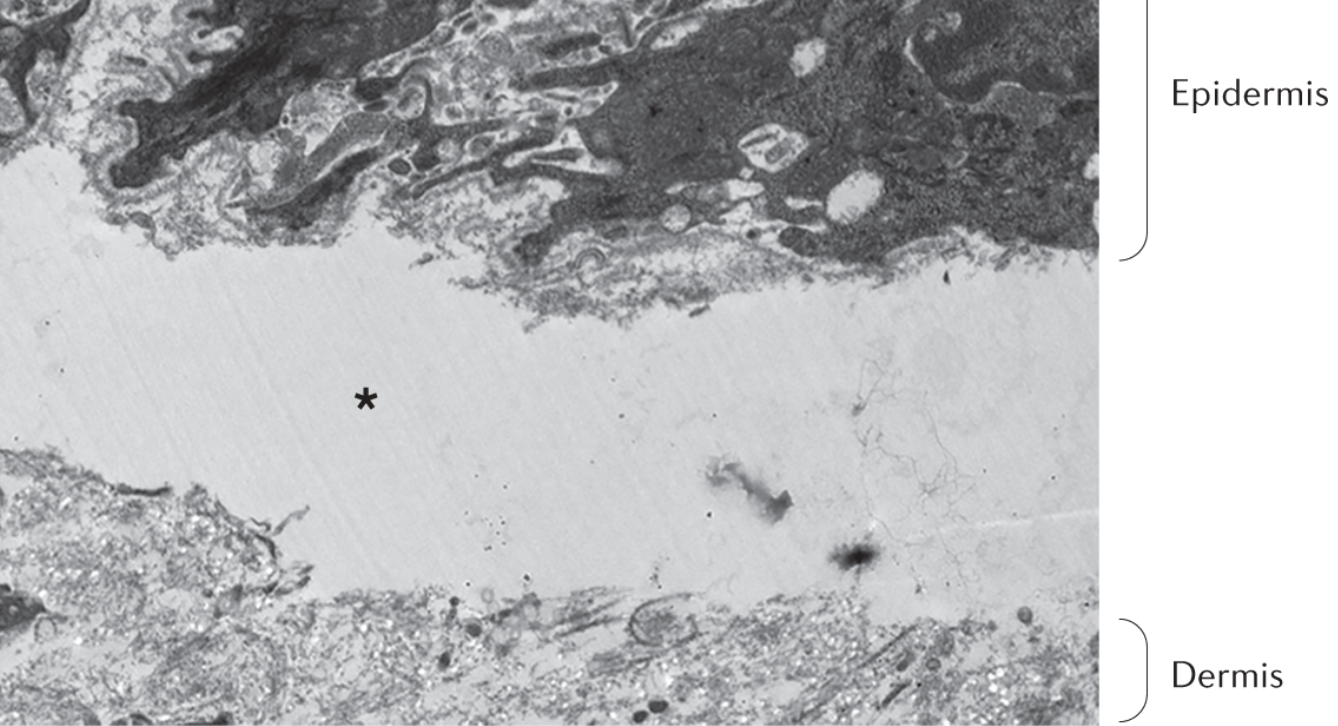

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) helps to observe the cutaneous basement membrane zone more precisely than light microscopy: leading to distinguishing where the separation of the skin tissue occurs so that we can categorise the EB skin samples into four conventional groups of EB, including :

- Simplex EB

Epidermolysis bullosa simplex is characterised by aggregation of keratin tonofilaments in basal keratinocytes and the cleavage(asterisk) resulting in fragile keratin -cytoskeleton. The cleavage problem occurs beneath the nucleus of basal cells in the epidermis. (4,10)

Junctional EB

Junctional EB is characterised by a cleavage (asterisk) via the lamina lucida (10)

- Dystrophic EB TEM features

Dystrophic EB is characterised by a cleavage (asterisk) under the Lamina densa, and also, we can see there are no anchoring fibrils. (10)

- Kindler EB TEM features

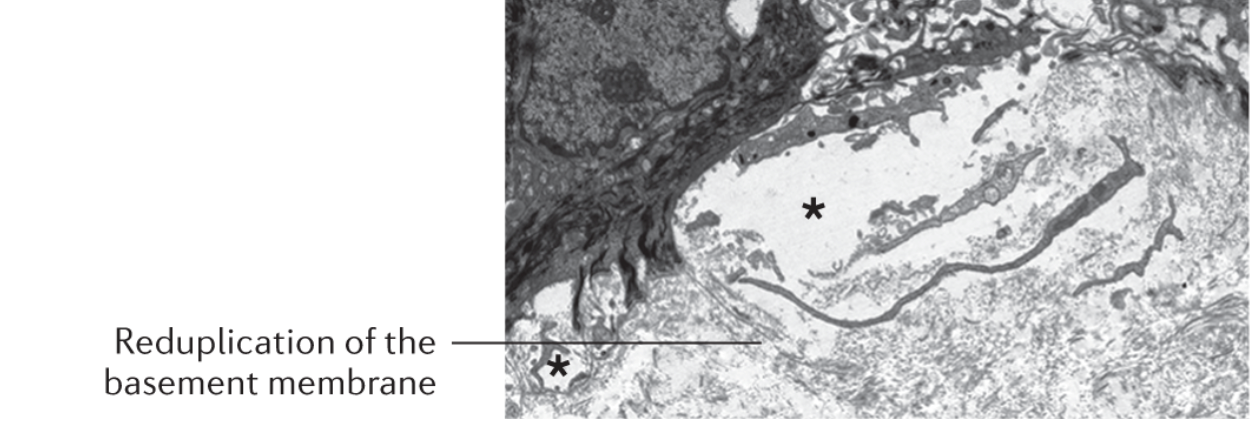

Kindler EB is characterised by “Reduplication of basement membrane” and multiple cleavages (asterisk) in various skin layers. (10)

Treatment

A definitive cure for EB remains elusive, and the existing treatments are primarily focused on effectively managing the complications associated with this condition. Nevertheless, ongoing research in translational therapies explores the possibility of targeting the affected genes and proteins within cells. With that said, let us now turn our attention to the various strategies employed in the management of EB.

Pain and itching management in EB

Pain and itch are two common symptoms in EB patients, requiring comprehensive management strategies. Pain can stem from various sources, including the skin, mucosae, bones, muscles, dental problems, constipation, and neuropathic pain. A multimodal approach, encompassing pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods, is crucial for effective pain relief and improved quality of life. Similarly, the itch is prevalent, particularly in recessive dystrophic EB, and can be refractory to conventional treatments. Neuropathic pain medications and non-pharmacological approaches can offer some relief.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux management in EB

As mentioned before is not only a skin disorder but can also affect other organs. In some cases, EB-related complications may impact the lower oesophageal sphincter, a muscle that helps prevent stomach acid from flowing back into the oesophagus. Treatment with H2 antagonists or proton pump inhibitors is generally recommended to manage EB-RELATED gastroesophageal refluxes. People with dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB) may experience dysphagia, a condition characterised by difficulty swallowing due to oesophageal blistering and webs, leading to pain and discomfort. To manage dysphagia, a combination of strategies is recommended, including the consumption of fluids and soft-textured foods and painkillers to alleviate discomfort.

Additionally, short-term oral corticosteroids can be considered to reduce swelling of the mucosal lining in the oesophagus. Oesophageal strictures are frequently observed in individuals with dystrophic EB and may necessitate medical intervention, such as endoscopic or radiological dilatations using balloon dilators that apply radial force. These dilatations may require periodic repetition for optimal results. In situations where symptoms like vomiting, abdominal distention, and a lack of faecal output are evident, medical professionals should consider the possibility of pyloric atresia and evaluate the need for surgical correction in those with EB.

Genitourinary issues management in EB

Genitourinary tract involvement can accompany severe forms of EB, leading to complications such as meatal or urethral stenosis, hydroureter, hydronephrosis, and vaginal stenosis. Renal parenchymal diseases like post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, IgA nephropathy, and renal amyloidosis can also occur, potentially leading to renal impairment and end-stage kidney disease. Management of these complications often involves dialysis or renal transplantation.

Musculoskeletal issues management in EB

Musculoskeletal issues, such as osteopenia, osteoporosis, and bony fractures, are frequently observed in severe EB cases, primarily attributed to reduced physical activity, delayed puberty, chronic inflammation, and low vitamin D levels. Calcium and vitamin D supplementation, weight-bearing exercise promotion, and intervention to induce puberty have been recommended to combat these challenges. While oral or intravenous bisphosphonates have been used, further research is needed to ascertain their effectiveness in improving bone mineral density and preventing fractures.

Severe forms of EB, particularly recessive dystrophic EB, can lead to progressive hand deformities, significantly impacting hand function. Preventive measures, including the use of dressings, bandages, and specialised gloves to prevent web spaces from fusing, are crucial in managing these deformities. Surgical release with skin grafting may be required in severe cases, followed by postoperative hand therapy for functional maintenance. Similarly, localised forms of EB can cause painful plantar keratoderma, affecting gait and leading to musculoskeletal changes. Podiatry assessment and intervention are essential components of managing such complications. (10)

Skin wound management in EB

Bathing aids in the gentle removal of dressings that may float away in the water. During bathing, patients can use an antimicrobial wash. However, to prevent antibiotic resistance m, systematic antibiotics will be reserved for the worst-case situation where the wounds won’t heal. Wound care is carried out using non-adherent soft silicone dressings and thin polyurethane-soft silicone foams. In addition to this, haemorrhagic blisters can be lanced and drained. Specialised soft silicone foams are used for hand dressing, and specific techniques are employed to separate fingers and prevent premature digit fusion. (10-11)

Treatment of mucosal squamous cell carcinoma in EB

In the case where patients develop mucosal squamous cell carcinoma, the treatment is radiotherapy and chemotherapy. In more severe cases, excision of the tumour might be helpful, although it leads to metastasis in most cases. (10,12)

Nutritional management of EB

Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB) presents significant challenges in nutrition management, particularly in severe forms of the condition. The presence of oral and dental issues, oesophageal strictures, and extensive skin wounds and inflammation severely limit food intake, necessitating the use of purees or liquids. In addition to impaired wound healing, these nutritional limitations can lead to failure to thrive, delayed puberty, hypoalbuminemia, and anaemia. Therefore, specialised dietetic input is essential to address these complications effectively. In managing EB, consideration must also be given to potential atopic complications that could further impact nutrition and overall health. (13-14)

Constipation management in EB

The prevalence of constipation in EB, especially in severe cases, requires careful management due to various contributing factors, including recurrent anal blistering and fissures, low dietary fibre and fluid intake, and the use of constipating drugs. Osmotic laxatives, such as polyethylene glycol, are often necessary to alleviate constipation. Moreover, chronic protein-losing enteropathy and blood loss from intestinal erosions in junctional EB can exacerbate malnutrition and anaemia. To address these gastrointestinal challenges, a low medium-chain triglyceride-based diet or the use of prednisolone may be beneficial. (15-16)

Anaemia management in EB

Anaemia is a common complication in severe EB cases, resulting from iron deficiency due to limited dietary intake and increased losses through the gastrointestinal tract. Additionally, chronic inflammation in EB contributes to anaemia of chronic disease. The management of anaemia in EB requires a tailored approach, as oral iron supplements may be poorly tolerated due to constipation. In severe cases, intravenous iron supplements may be necessary, and blood transfusions are reserved for severe anaemia. (17-18)

Head &neck issues management in EB

Various head and neck complications can arise in EB patients, with ocular issues being particularly common. Treatment for ocular complications should be tailored to address specific pathologies. Prophylactic use of lubricating eye drops and ointments can be beneficial, especially in severe cases or when eyelid or corneal integrity is compromised. Laryngeal involvement, presenting as hoarseness, stridor, or respiratory obstruction, is frequently observed in severe junctional EB and other severe forms. Nebulised corticosteroids can be effective in managing acute episodes, while tracheostomy may be necessary in severe and chronic cases. (19-21)

Cardiovascular issues management in EB

Dilated cardiomyopathy is a specific feature of autosomal dominant EB simplex due to dominant KLHL24 mutations. In some cases, severe forms of EB may also lead to cardiomyopathy, with various contributing factors. Early identification and appropriate management of cardiac issues are critical. While medical management can help alleviate cardiomyopathy for some, the progressive disease may still pose life-threatening risks. (22-24)

Articles on Misdiagnosis

Wang Z, Lin Y, Duan XW, Hang HY, Zhang X, Li LL. Misdiagnosed dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2021 May 6;9(13):3090-3094. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i13.3090. PMID: 33969095; PMCID: PMC8080732.

Delgado-Miguel C, Miguel-Ferrero M, De Lucas-Laguna R. Misdiagnosis in Epidermolysis Bullosa: Yet Another Burden on Patients and their Families. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022 Oct 26:S0001-7310(22)00904-8. English, Spanish. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2022.03.024. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36309044.

References

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………

1)Prasad AN. Epidermolysis bullosae. Med J Armed Forces India. 2011 Apr;67(2):165-6. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(11)60024-5. Epub 2011 Jul 21. PMID: 27365791; PMCID: PMC4920676.

2)Korte EWH, Welponer T, Kottner J, van der Werf S, van den Akker PC, Horváth B, Kiritsi D, Laimer M, Pasmooij AMG, Wally V, Bolling MC. Heterogeneity of Reported Outcomes in Epidermolysis Bullosa Clinical Research: A Scoping Review as a First Step Towards Outcome Harmonisation. Br J Dermatol. 2023 Apr 25:ljad077. doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad077. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37098154.

3)Has C, Bauer JW, Bodemer C, Bolling MC, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Diem A, Fine JD, Heagerty A, Hovnanian A, Marinkovich MP, Martinez AE, McGrath JA, Moss C, Murrell DF, Palisson F, Schwieger-Briel A, Sprecher E, Tamai K, Uitto J, Woodley DT, Zambruno G, Mellerio JE. Consensus reclassification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa and other disorders with skin fragility. Br J Dermatol. 2020 Oct;183(4):614-627. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18921. Epub 2020 Mar 11. PMID: 32017015.

4)Has C, Liu L, Bolling MC, Charlesworth AV, El Hachem M, Escámez MJ, Fuentes I, Büchel S, Hiremagalore R, Pohla-Gubo G, van den Akker PC, Wertheim-Tysarowska K, Zambruno G. Clinical practice guidelines for laboratory diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa. Br J Dermatol. 2020 Mar;182(3):574-592. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18128. Epub 2019 Aug 9. PMID: 31090061; PMCID: PMC7064925.

5)Jonkman MF, Pas HH, Nijenhuis M, Kloosterhuis G, Steege G. Deletion of a cytoplasmic domain of integrin beta4 causes epidermolysis bullosa simplex. J Invest Dermatol. 2002 Dec;119(6):1275-81. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.19609.x. PMID: 12485428.

6)Fontao L, Tasanen K, Huber M, Hohl D, Koster J, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Sonnenberg A, Borradori L. Molecular consequences of deletion of the cytoplasmic domain of bullous pemphigoid 180 in a patient with predominant features of epidermolysis bullosa simplex. J Invest Dermatol. 2004 Jan;122(1):65-72. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2003.22125.x. PMID: 14962091.

7)Shinkuma S. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: a review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015 May 26;8:275-84. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S54681. PMID: 26064063; PMCID: PMC4451851.

8)Akasaka E, Nakano H, Sawamura D. Kindler epidermolysis bullosa associated with oral cancer in the buccal mucosa. JAAD Case Rep. 2022 Jun 18;26:13-16. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.06.005. PMID: 35815233; PMCID: PMC9263402.

9)Fassihi H, McGrath JA. Prenatal diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa. Dermatol Clin. 2010 Apr;28(2):231-7, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2010.02.001. PMID: 20447485.

10)Bardhan, A., Bruckner-Tuderman, L., Chapple, I.L.C. et al. Epidermolysis bullosa. Nat Rev Dis Primers 6, 78 (2020).

11)El Hachem, M., Zambruno, G., Bourdon-Lanoy, E. et al. Multicentre consensus recommendations for skin care in inherited epidermolysis bullosa. Orphanet J Rare Dis 9, 76 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-9-76

12)Mellerio JE, Robertson SJ, Bernardis C, Diem A, Fine JD, George R, Goldberg D, Halmos GB, Harries M, Jonkman MF, Lucky A, Martinez AE, Maubec E, Morris S, Murrell DF, Palisson F, Pillay EI, Robson A, Salas-Alanis JC, McGrath JA. Management of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in patients with epidermolysis bullosa: best clinical practice guidelines. Br J Dermatol. 2016 Jan;174(1):56-67. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14104. Epub 2015 Nov 7. PMID: 26302137.

13)Haynes, L. Nutrition for children with epidermolysis bullosa. Dermatol. Clin. 28, 289–301 (2010).

14)Haynes, L., Mellerio, J. E. & Martinez, A. E. Gastrostomy tube feeding in children with epidermolysis bullosa: consideration of key issues. Pediatr. Dermatol. 29, 277–284 (2012).

15)Hubbard, L., Haynes, L., Sklar, M., Martinez, A. E. & Mellerio, J. E. The challenges of meeting nutritional requirements in children and adults with epidermolysis bullosa: proceedings of a multidisciplinary team study day. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 36, 579–584 (2011).

16)Freeman, E. B. et al. Gastrointestinal complications of epidermolysis bullosa in children. Br. J. Dermatol. 158, 1308–1314 (2008).

17)Hwang, S. J. E., Daniel, B. S., Fergie, B., Davey, J. & Murrell, D. F. Prevalence of anemia in patients with epidermolysis bullosa registered in Australia. Int. J. Womens Dermatol. 1, 37–40 (2015).

18)Kuo, D. J., Bruckner, A. L. & Jeng, M. R. Darbepoetin alfa and ferric gluconate ameliorate the anemia associated with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Pediatr. Dermatol. 23, 580–585 (2006).

19)Fine, J.-D. et al. Eye involvement in inherited epidermolysis bullosa: experience of the National Epidermolysis Bullosa Registry. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 138, 254–262 (2004).

20)Fine, J.-D., Johnson, L. B., Weiner, M. & Suchindran, C. Tracheolaryngeal complications of inherited epidermolysis bullosa: cumulative experience of the national epidermolysis bullosa registry. Laryngoscope. 117, 1652–1660 (2007).

21)Hore, I. et al. The management of general and disease specific ENT problems in children with epidermolysis bullosa — a retrospective case note review. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 71, 385–391 (2007).

22)Schwieger-Briel, A. et al. Epidermolysis bullosa simplex with KLHL24 mutations is associated with dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Invest. Dermatol. 139, 244–249 (2019).

23)Ryan, T. D. et al. Ventricular dysfunction and aortic dilation in patients with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Br. J. Dermatol. 174, 671–673 (2016).

24)Bolling, M. C. et al. PLEC1 mutations underlie adult-onset dilated cardiomyopathy in epidermolysis bullosa simplex with muscular dystrophy. J. Invest. Dermatol. 130, 1178–1181 (2010).

Provided and edited by the members of MARI authors; Parisa K Biomedical Science BSc, Anahita Arfa MSc, and Pooya Beigi MD.

Mini Disclaimer

User discretion: The material presented here is for your information and to be used for your reference only. Our volunteers have sourced this information from reputable sources and made sure it meets the quality standards at MARI. The information presented is not intended to be used as a diagnostic tool, a basis upon which to make diagnostic decisions, or to substitute the advice of a medical or healthcare professional.

If you are a patient experiencing any of the listed symptoms, please consult a healthcare provider for specialised care and follow the instructions provided for you by your doctor. If you are in the US and would like advice on a possible case leading to errors in medicine, please reach out to our MARI Consultation team.