Understanding Multiple System Atroph

Objective: This article aims to educate individuals with Multiple System Atrophy, their support network, and clinicians on the disease’s symptoms, diagnosis process, treatment strategies, and available resources to improve care and management.

Symptoms and Progression of MSA

Introduction

Multiple System Atrophy (MSA) is a rare and progressive neurodegenerative disorder with symptoms commonly emerging during adulthood in the fifth to sixth decade of life with a mean life expectancy of 6-10 years post-diagnosis (Lee et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2024; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [NINDS], 2024). This condition is defined by a combination of parkinsonism, cerebellar ataxia, and autonomic dysfunction, with two subtypes: MSA-P, characterized by parkinsonian symptoms, and MSA-C, characterized by cerebellar symptoms (Nandanwar & Truong, 2024). The global prevalence of MSA is estimated to range from 1.9 to 4.9 cases per 100,000 individuals (Nandanwar & Truong, 2024). Although MSA is considered rare, understanding this disorder is critical due to its severe impact on patients’ quality of life and its complex clinical presentation, which tends to lead to misdiagnosis and delays in treatment (Nandanwar & Truong, 2024).

Although the underlying cause of MSA remains unclear, as most cases generally occur sporadically, it is suggested that a combination of genetic and environmental factors contribute to its development (Tseng et al., 2023; NINDS, 2024). Variants in genes associated with oxidative stress and inflammation have been implicated in increasing susceptibility to MSA; however, no definitive causative gene has been identified (NINDS, 2024). Additionally, exposure to environmental toxins, including metal dust, smoke, plastic chemicals, organic solvents, and pesticides, has been proposed as a potential risk factor, possibly by influencing epigenetic mechanisms, although further studies are needed to confirm these findings (Tseng et al., 2023).

Symptoms and Progression of MSA

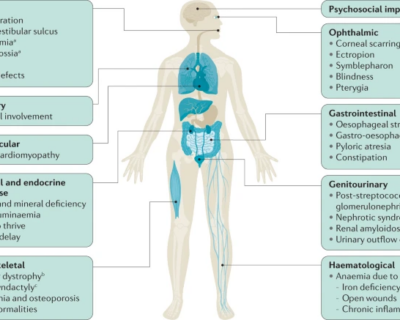

MSA is classified into two primary subtypes:

- MSA-P: Characterized by Parkinsonian features such as rigidity, bradykinesia, tremors, and postural or gait instability (Liu et al., 2024).

- MSA-C: Characterized by cerebellar ataxia, leading to impairments in speech, eye movements, and walking due to limb ataxia (Liu et al., 2024).

Autonomic dysfunction, common to both subtypes, can include symptoms such as orthostatic hypotension, urinary incontinence, and sexual dysfunction (Goolla et al., 2023).

The progression of multiple system atrophy involves a combination of pathological processes, including the accumulation of abnormal proteins, disruptions in synaptic function, imbalances in protein homeostasis, inflammation within neurons, and eventual neuronal cell death (Liu et al., 2024).

Clinical Diagnosis Process

Diagnosing MSA can be a complex process due to the overlap of symptoms with other neurological disorders, particularly Parkinson’s disease (NINDS, 2024). This symptom similarity tends to lead to misdiagnosis and delay treatment and management strategies (Palma et al., 2018). Individuals with MSA may initially be misdiagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and treated with Parkinson’s medications. The lack of symptom relief from these drugs can provide an important diagnostic clue for MSA (NINDS, 2024).

Key distinguishing feature: One unique characteristic of MSA is the accumulation of the protein alpha-synuclein in glial cells, specifically in oligodendrocytes, which are responsible for producing myelin (NINDS, 2024). Myelin acts as a protective sheath that facilitates efficient electrical signalling between nerve cells. In contrast, Parkinson’s disease involves alpha-synuclein accumulation within nerve cells rather than glial cells. Despite these differences, both conditions are categorized as “synucleinopathies” because of the shared presence of alpha-synuclein aggregation, further complicating the differentiation between the two disorders (NINDS, 2024).

Diagnostic tools:

- Clinical examination: Physicians assess motor symptoms, autonomic dysfunction, and other neurological signs characteristic of MSA (NINDS, 2024).

- Imaging techniques: MRI scans are critical in identifying structural changes in the brain, such as atrophy in specific regions like the pons, cerebellum or putamen, which are indicative of MSA (Liu et al., 2024; NINDS, 2024). Dopamine transporter (DaT) scans can also be used to evaluate the abnormal distribution and activity of dopamine in the brain (NINDS, 2024).

- Autonomic function tests: Tests evaluating blood pressure regulation, heart rate variability, and bladder function help detect autonomic nervous system involvement (Palma et al., 2018; NINDS, 2024).

Despite advances in diagnostic tools and criteria, accurately diagnosing MSA remains challenging, especially in its early stages (Palma et al., 2018). As a result, diagnosis often relies on clinical judgment and the exclusion of other conditions.

Current Treatment Options

Currently, there is no cure for MSA that can halt or slow its progression. The focus of treatment remains on managing symptoms to improve the patient’s quality of life (Liu et al., 2024). These treatments aim to alleviate some of the challenges posed by MSA but do not address the underlying disease processes.

Medications:

- Levodopa is commonly used to stimulate dopamine receptors and improve motor function, but its effects are short-lived (NINDS, 2024).

- Blood pressure stabilizers are prescribed, and lifestyle changes such as adding salt to meals, maintaining good hydration, and consuming lighter meals are advised for managing orthostatic hypotension (NINDS, 2024).

Botox injections: Botox injections can be used to treat symptoms such as muscle spasticity or abnormal postures by relaxing the affected muscles (NINDS, 2024).

Physical and occupational therapy: Physical therapy is recommended to improve mobility, balance, and reduce rigidity, while occupational therapy can help patients adapt to daily tasks such as dressing, cooking, and eating (NINDS, 2024).

Despite the absence of a cure, ongoing research and clinical trials are investigating treatments that target neuroinflammation, immunotherapy approaches to address protein aggregation, and the potential of stem cell therapies (Watanabe et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2024).

Living with MSA: Help and Resources

Mission MSA

Conclusion

MSA continues to remain a complex and challenging disorder, with no definitive treatment available. While diagnosis continues to be difficult, advances in imaging and clinical assessments are improving early detection. Symptom management is crucial for maintaining daily function, and emerging therapies may provide hope for more effective treatments in the future. Ongoing research into disease-modifying options is essential to advancing care and outcomes for those affected by MSA.

References

Goolla, M., Cheshire, W. P., Ross, O. A., & Kondru, N. (2023). Diagnosing multiple system atrophy: Current clinical guidance and emerging molecular biomarkers. Frontiers in Neurology, 14, Article 1210220. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1210220

Lee, H., Ricarte, D., Ortiz, D., & Lee, S. (2019). Models of multiple system atrophy. Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 51(11), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-019-0346-8

Liu, M., Wang, Z., & Shang, H. (2024). Multiple system atrophy: An update and emerging directions of biomarkers and clinical trials. Journal of Neurology, 271(5), 2324–2344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-024-12269-5

Nandanwar, D., & Truong, D. D. (2024). Multiple system atrophy: Diagnostic challenges and a proposed diagnostic algorithm. Clinical Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 11, 100271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prdoa.2024.100271

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2024). Multiple system atrophy. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/multiple-system-atrophy

Palma, J., Norcliffe-Kaufmann, L., & Kaufmann, H. (2018). Diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Autonomic Neuroscience, 211, 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2017.10.007

Tseng, F. S., Foo, J. Q. X., Mai, A. S., & Tan, E. (2023). The genetic basis of multiple system atrophy. Journal of Translational Medicine, 21(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-03905-1

Watanabe, H., Shima, S., Mizutani, Y., Ueda, A., & Ito, M. (2023). Multiple system atrophy: Advances in diagnosis and therapy. Journal of Movement Disorders, 16(1), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.14802/jmd.22082

Provided and edited by the members of MARI Research, Error in Medicine Foundation and MISMEDICINE Research Institute, including Rojina Nariman, Helia Falahatkar and Dr. Pooya Beigi MD. MSc.